The Race to End All Races

A TRACK TO TEST THE LIMITS OF MAN & MACHINE.

The 24 Hours of Le Mans was created to test the limits of manufacturers to increase dependability and efficiency of their vehicles, thusly requiring homologation of race cars so the technology flowed down to street cars. The race has occurred annually since 1923 making it the oldest, still active race of its kind. This sort of tenure has created for the race a sort of prestige and worldwide coverage and acknowledgement, although the race is held in, you guessed it, Le Mans, France. The race can oftentimes be referred to as the “Grand Prix of Endurance and Efficiency” due to its running for 24 hours straight, thus testing both the endurance of man and efficiency of machine.

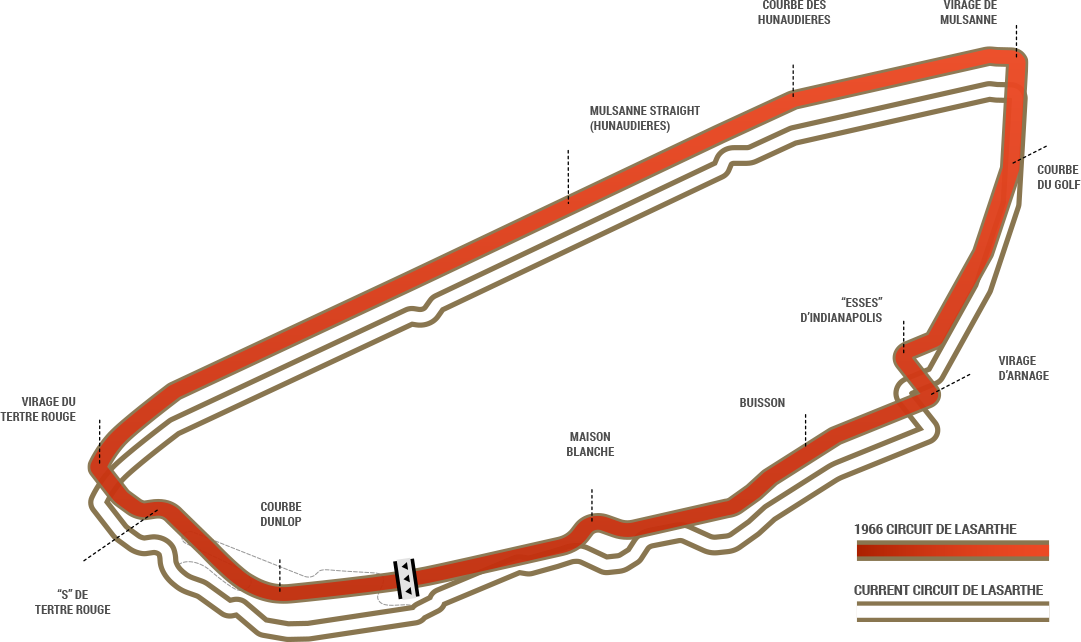

The track, the Circuit de la Sarthe, is part race track and part public roads. That means, part of the track is well maintained, while the public roads may not adhere to the same strict maintenance, testing chassis rigidity and suspension reliability. Also, the famous Mulsanne Straight is a lengthy one pushing manufacturers and builders to place more emphasis on aerodynamics to keep the car planted. On this page you’ll find the history of the race, the GT40’s competitors in the ‘66 Le Mans, explanation of the highly debated finish and a turn-by-turn look at the Circuit de la Sarthe.

The race has occurred annually since 1923 making it the oldest, still active race of its kind.

The History

The 24 Hours of Le Mans first ran on May 26-27, 1923, through public roads around Le Mans. - with a winner being declared by the car which could go the farthest distance over three consecutive 24-hour races. A field of 33 cars from 18 different makes headed off for their round-the-clock adventure. Lagache and Léonard ran out as winners in their Chenard-Walker, covering a distance of 1,732 miles at an average of just over 57 MPH. No fewer than 30 of 33 starters crossed the finish line, which must rank as an all-time record for the event.

Since Le Mans was created to test the reliability of the machine, in part, it was required for decades the cars had to run at least an hour before replenishing any fluids.

Another rule unique to Le Mans is that cars must be shut off during refuels for safety, but also to further test the reliability of the car’s engine by having to turnover again. (image of pit stop)

Other items unique to Le Mans culture is the waving of the French tricolor to start the race, which is oftentimes followed by a fly-over of jets trailing blue, white and red smoke.

A tradition also spawned at Le Mans is the waving of safety flags during the final lap from workers congratulating the winning car.

The spraying of champagne arguably first happened at Le Mans when Dan Gurney first did so at the ‘67 Le Mans. Gurney saw Henry Ford II and team owner Carroll Shelby standing around the podium with their wives, and out of spite due to rumors of a predicted disaster, shook the magnum of champagne to spray everyone nearby. Porsche racer Jo Siffert, winner of the two-liter prototype class, joined in, with AJ Foyt laughing out loud. From that moment, nearly every major race winner has emulated Gurney's creative Le Mans victory celebration.

The infamous Le Mans start - Originally, drivers lined up across from their cars and once the flag dropped had to sprint to their car, hop in, turn it over and get going.

This led to drivers not buckling up to save time. So, in 1970, drivers were buckled in then blasted off after the flag dropped. They lined up per their qualifying time.

Because of the 1966 highly debated finish, which was ruled due to the No. 2 car traveling a greater distance due to starting further back, it was ruled in 1971 that car begin from a rolling start and that the car that completes the greatest number of laps wins.

History of the Track

Since 1923, the Circuit de la Sarthe has served as the proving grounds for the world’s fastest drivers and cars at the 24 Hours of Le Mans. The track consists of both permanent track and public roads that close temporarily for the race and has changed drastically since the inaugural race. The track now spans 13.629 km (8.469 mi) and initially entered the town of Le Mans, however, was cut short in order to protect onlookers. The circuit is one of the longest in the world and has a capacity of seating 100,000 fans.

The first races were held in 1920. The UMF (Union Motorcycliste de France) organized a motorcycle race on a triangular course from the Pontilieue suburbs of Le Mans, then along public roads to Mulsanne and back again. In total, the circuit was over 10 miles long. It proved extremely challenging with only four motorcyclists completing the race out of 33 that entered. After the excitement surrounding the event, motorcycle races continued to be held at the track, In 1922, the idea of the 24-hour race was born when the secretary of the ACO (Automobile Club de l’Ouest) received an offer from the French subsidiary of the Rudge Whitworth wheels company of 100,000 Francs. The offer was made to organize a race with the money becoming the prize fund to entice racers to come out and compete.

Before jumping in head-first, Durand thought long and hard about the race. Then he realized he had a real opportunity to serve the public - in that he would pit manufacturer against manufacturer in the ultimate test of speed and stamina. He spoke with ACO president Gustave Singher and journalist Chrales Faroux about his proposal. Faroux actually advocated for a 24-hour race. Thus, the 24-hour race was officially born on the makeshift track using public roads and prepped race track. Faroux would handle drawing up the rules and regulations.

By May 26,1923, 33 cars from 18 different makes lined up to take the green flag and the first 24-hour race at Le Mans was underway. Surprisingly, 30 of the 33 cars crossed the finish line with the winner covering a distance of 1,732 miles at an average of just over 57 MPH. Then, annually, the 24-hour race was held at Le Mans. The race continued to use this first course with gradual improvement. And that brings us to the ‘66 Le Mans where P/1046 competed.

1966 Circuit de la Sarthe: Turn-by-Turn

Throughout the years of operation, the track was revised to tame speeds and protect spectators, amongst other things. In 1968, a chicane was added just before the pit entrance.

What was good for the GT40 was that the additional chicanes were not installed until 1968, allowing the fury of the GT40 to be fully extracted - to stretch its legs - down the Mulsanne Straight - a factor pivotal in its ‘66 win. Now, since we’re focusing on the 1966 race, we’re look deeper into the track layout in 1966.

The Competitors

Goal #1 - Dethrone Ferrari.

After Henry II’s potential deal fell through with Enzo Ferrari, it was game on. Millions of dollars and countless hours of development were invested in creating a foe the prancing horse couldn’t touch. The results? Well, you probably know the history by now.

Ferrari 330 P3

Wheelbase: 95in.

Weight: 1,600 lbs.

Engine: Type 216 V2

Power: 420 horsepower

Power-to-Weight: 0.263 hp/lb

Top Speed: 186 mph

Ferrari’s Prototype entry and direct competitor of the GT40 was a powerful and lightweight sports car, yet lacked the reliability to conquer at a 24-hour endurance race. Oftentimes described as the most beautiful race car of all time, the Ferrari 330 P3 was definitely a looker, but its performance on track was underwhelming. Three 330P3s were entered into the ‘66 race yet none finished leaving Ford to battle it out with Porsche.

Development

Between 1960 and 1965, Ferrari dominated the 24 Hours of Le Mans. The Ferrari P Series were sports prototype racing cars produced in the ‘60s and early ‘70s. Ferrari began producing mid-engine racing cars in 1960 with the Ferrari Dino V6 engine. The first evolution of P cars was the 250 P debuting in ‘63, which won the 12 Hours of Sebring, 1000 km Nurburgring and the 24 Hours of Le Mans that year. The 275P and 330P that followed were evolutions of this solid foundation, but featured longer wheelbases and 3.3L and 4.0L engines that raced in ‘63 and ‘64, respectively.

In 1965, two entirely new cars, the 275 P2 and 330 P2 featured a lower/lighter chassis and more aerodynamic bodies. The cars were outfitted with revamped versions of previous 275 and 330 V12 engines equipped with four camshafts producing 350 hp and 410 hp, respectively. The P2 cars were replaced with the P3 in ‘66.

Which brings us to the subject at hand, the stunning 330 P3. The 1966 P3 introduced fuel injection to the Ferraris. It also used a P3 (Type 593) transmission that was prone to failure and was replaced by the ZF transmission when P3 0844 and 0848 were converted to 412 Ps. Only three 330 P3s were built, and specifically for competition. There are no longer any Ferrari P3s existent as the original P3 0846 was converted to a P3/4 and P3s 0844 and 0848 were converted to 412 Ps by Ferrari.

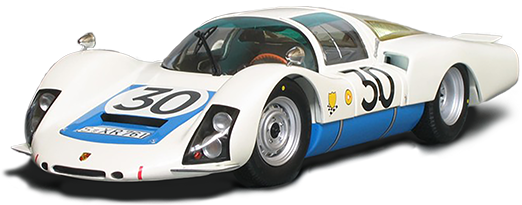

Porsche 906 Long Tail

Wheelbase: 90.6in.

Weight: 1,360 lbs.

Engine: 901/20 B6

Power: 225 horsepower

Power-to-Weight: 0.165 hp/lb

Top Speed: 175 mph

With Ferrari’s Prototype no longer a competitor in the ‘66 race due to mechanical failures, the GT40s only had the Porsche Prototypes in their rearview. The GT40 completed 360 laps, whereas the runner-up Porsche only completed 339 laps.

Porsche’s Prototype entry was the 906 (Carrera 6). The runner-up was the Long Tail variant of the 906. The long tail version was created specially for the long straight part of the Le Mans track to increase aerodynamics and high speed stability.

Development

Preceding the 906 was the 904 and 905. The 904 featured a strong but simple steel frame chassis which sacrificed weight in an effort for strength and ease of manufacturing to meet the homologation rule of 100 cars produced. Despite the weight, the car was powerful and handled beautifully, yet just couldn’t compete with Ferrari’s lightweight Dino. So, back to the drawing board it was and the 904’s ladder frame was replaced with a lighter space frame construction. 13” wheels were fitted that were purchased from Lotus to lower the vehicle and a flat eight Grand Prix engine was installed.

By the time of the development of the 905, the FIA reduced homologation numbers from 100 to 50. This allowed manufacturers to focus more on the racecar design and development than actual production. First on the list was to get the space frame construction up to the same rigidity level of the 904. Once that was accomplished, 904 suspension was fitted since it already proved itself capable.The remainder of the time was spent on lightweighting and tuning of the flat six. Where aluminum was originally used, magnesium replaced it and steel bits were replaced with titanium. The crankshaft was forged steel and the engine featured an 80mm bore and 66 mm stroke displacing the motor to 1,991 cubic centimeters and a 10.3:1 compression ratio. It could climb to 8,000 RPM producing around 225 horsepower and 145 lb-ft. of torque. It was also lighter than the 904’s four-cylinder. The engine was mated to a 5-speed, fully-synchronized transmission. Now that the car was together, it was to the wind tunnel it went where drag was only slightly increased no thanks to a larger nose, which did provide more downforce at high speeds - like the Mulsanne Straight would throw at it. A plexiglass cover was used for the engine to further lighten the body and help with weight balance.

The six-cylinder engined 904/6 model received chassis numbers starting with ‘906’ to distinguish the latest racecar. Internally, marketing teams were dubbing the previous cars Carrera 904 and 905, so naturally, this car was referred to as the Carrera 6. The car made its competition debut in January 1966 at the Daytona 24 Hours. Garnering a sixth place finish overall and a class win, the Germans were back on time and ready to prove their worth to Ferrari at Le Mans. Shortly after, all 50 homologated cars were spoken for.

Here’s where the prototype car comes into play. Once all 50 cars were sold, efforts were made to make the 906 better, most importantly, a switch to Bosch fuel injection over carburetion, which didn’t outright make more power, but did improve throttle response. These revised cars were dubbed 906E for Einspritzung, or “injection”. The bodywork was also revised which brought drag levels back down to the arena of the 904 without sacrificing downforce. Because of the fuel injection, the 906 was now forced to run in the prototype class. One of the first outings for the new car was the 1966 Le Mans where the cars placed 4th, 5th, 6th and 7th.

Ferrari 275 GTB/C

Wheelbase: 94.5 in.

Weight: 2,452 lbs.

Engine: Type 213 V2

Power: 290 horsepower

Power-to-Weight: 0.118 hp/lb

Top Speed: 171 mph

Although not a direct competitor of the GT40, this was the fastest Ferrari on the Circuit de la Sarthe during the 1966 Le Mans. Ferrari’s GT entry at least finished the race, something the Ferrari Prototypes can’t say these 50 years later. However, the 275 GTB/C still gave the leading cars a run for their money snagging 8th position (No. 29 car) at the ‘66 Le Mans and secured Ferrari as the overall third placing manufacturer.

Development

For the 1964 race season, Ferrari’s 250 GT0 was beginning to show its age after several losses to Shelby’s Cobra Daytona. The reason being because of the FIA refusing to homologate the mid-engined 250 GTO LM due to limited numbers, so Ferrari had to re-skin the GTO. This was after Enzo Ferrari threatened to leave the motor sport and the FIA compromised. A new body with cues inspired by the 250 LM were fitted to four old chassis and three new chassis were constructed and fitted with the ‘64-style body and the 250 LM engine.

After the race season, Ferrari wanted to launch a replacement for the 250 GTO, so it naturally became the basis for the 275 GTB. However, with fans gravitating more to prototype racing, less emphasis was placed on Ferrari’s GT racer. A batch of four special lightweight racers was constructed, but it faced homologation difficulties - mainly due to its weight being considerably less than the road-going cars. So, Ferrari increased the weight considerably and the four were homologated late in ‘65. Because of these problems, Ferrari decided to derive a competition car from the road-going car and not vice versa. Regular short-nose 275 GTBs were used and a batch of 11 cars were built - easily identifiable by extra vents in the rear wings.

That brings us up to speed with the 275 GTB/C - “C” designating “Competizione”. Twelve cars were constructed and resembled the road-going 275 GTB, yet every body panel was different to free up weight, and underneath, very little resembled a street car. The body panels were made of ultra-thin aluminum - designed by Scaglietti. Mauro Forghieri designed this special lightweight version of the 275 GTB chassis and regular suspension was fitted, albeit made stiffer by the addition of extra springs. The aluminum body panels were thinner than the Cobra and GTO, and it’s said that even leaning on them can dent them. However, this extreme attention to lightweighting netted Ferrari 331 pounds of weight reduction in the 275 GTB/C from the road-going car.

The GTB/C was powered by the 250 LM engine. Oddly enough, Ferrari didn’t mention to the governing body that the 275 GTB had a six-carb option, so only a three carb engine could be homologated. The rest of the drivetrain was similar to the 275 GTBs, but slightly strengthened.

Interesting to note, two of the twelve 275 GTB/Cs were sold as street cars with different wheels/tires. The race versions were fitted with Borrani wire wheels wrapped in Dunlop’s latest racing tire. However, these tires proved so sticky that during cornering, the load was breaking wires. After this, Ferrari never again fitted racecars with wire wheels.

The Story Behind Motorsports Most Debated Finish

With two GT40s on the lead lap, Ford dreamed up a nice publicity stunt, that, in theory, would have made for quite the spectacle. However, Ford’s intentions were not carried through leading to a highly debated finish requiring the race to initiate new rules for following races.

Ford decided that the Bruce McLaren/Chris Amon and Ken Miles/Denis Hulme cars should cross the finish line together, for two reasons: it would be the first time ever that a pair of cars would take the overall victory at Le Mans, which would drive home the point that the car, a Ford GT, and not a driver, had won the race. Secondly, it would make for a great publicity photo.

Ken Miles was leading and lifted off the gas allowing McLaren in the No. 2 car to get ahead as they crossed the finish line. It was ruled that McLaren’s GT40 would be crowned with the win because his car traveled a greater distance, having started several positions behind Miles’ GT40. Now, keep reading to see how historians and experts have settled the debate on the car that did indeed win - chassis P/1046.

The Finish

How is finish order determined? Originally, the car and team that covered the most distance within the 24 hours was awarded the victory. However, the greatest distance rule was changed with the introduction of the rolling start in 1971. Now, the car that completes the greatest number of laps, soonest, wins.

Ford entered three factory cars under the Shelby-American, Inc. team name. The No. 1 car would be driven by Ken Miles and Denny Hulme. Hulme would be brought in just before Le Mans after Lloyd Ruby suffered injuries in a plane accident. The No. 2 car would be driven by a pair of New Zealanders - Bruce McLaren and Chris Amon. The third entry would list Dan Gurney and Jerry Grant as its drivers.

At the end of qualifying, the first four positions on the grid would be occupied by GT40 Mk. IIs. Dan Gurney and Jerry Grant would have the pole having set a lap time of 3:30.600 around the 8.38 mile circuit. Ken Miles and Denny Hulme would start in the 2nd position on the grid. The third Ford factory entry of McLaren and Amon would also start on the grid ahead of the first of the Ferraris. The No. 2 GT40 would start in the 4th position on the grid.

With a sweep of the top 3 spots secured well before the final lap Ford gave the drivers instructions to slow their lap times and to not race one another. Lest disaster strike via a failed component or even worse, a crash. According to Chris Amon, at the time of the instructions P/1046 piloted by Bruce Mclaren was around 50 seconds ahead of next Ford. However, Ken Miles continued a pace and caught, and passed, the #2.

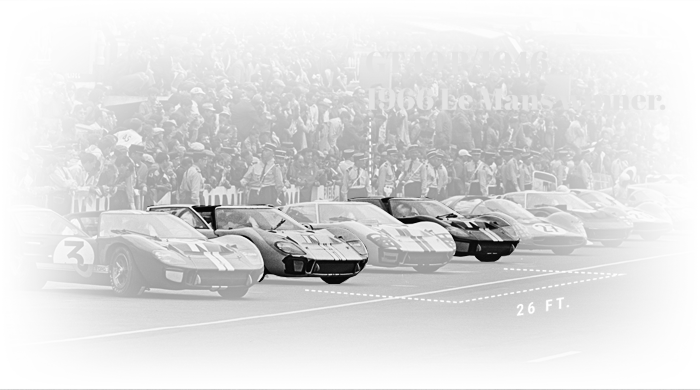

The powers-that-be at Ford further decided that a photo-finish would serve the Ford PR machine. Teams were given instructions cars to group, thus requiring the leader Ken Miles to slow. What is the significance of these facts? It is the basis of the controversy – the margin of victory recorded by the Automobile Club de l’Ouest, the governing body of Le Mans, was eight meters, or just over 26 feet. The winner declared as the No. 2 GT40 driven by Amon/McClaren. The difference of 26 feet was determined by the fact that McLaren/Amon started further back from Miles’ team. First place was awarded to chassis P/1046 based on the “distance” rule.

However, the reality to this controversy is much simpler. As Chris Amon recently stated "At pace we would have won Le Mans". P/1046 was on pace to win before team orders were given to slow down well before the finish. So while controversy over the finish exists, the reality is: P/1046 was the rightful champion.

GT40 P/1046. 1966 Le Mans winner.

The reality to this controversy is much simpler.

As Chris Amon recently stated "At pace we would have won Le Mans". P/1046 was on pace to win before team orders were given to slow down well before the finish. So while controversy over the finish exists, the reality is: P/1046 was the rightful champion.